For years, manga has been celebrated all around the world and has played a big part in Japan’s cultural identity. These illustrated and immersive storybooks range in style and genre and there are many suitable for readers of various ages. Manga makes up a substantial chunk of Japan’s economy and, with fans spread across the globe, remains a major cultural export. Yet, what many people may not know is that the origins of this seemingly new global phenomenon actually date back centuries.

While there is no exact date that marks the beginning of the manga, many historians have referenced a few key examples and dates that they believe played a role in influencing what we call manga today.

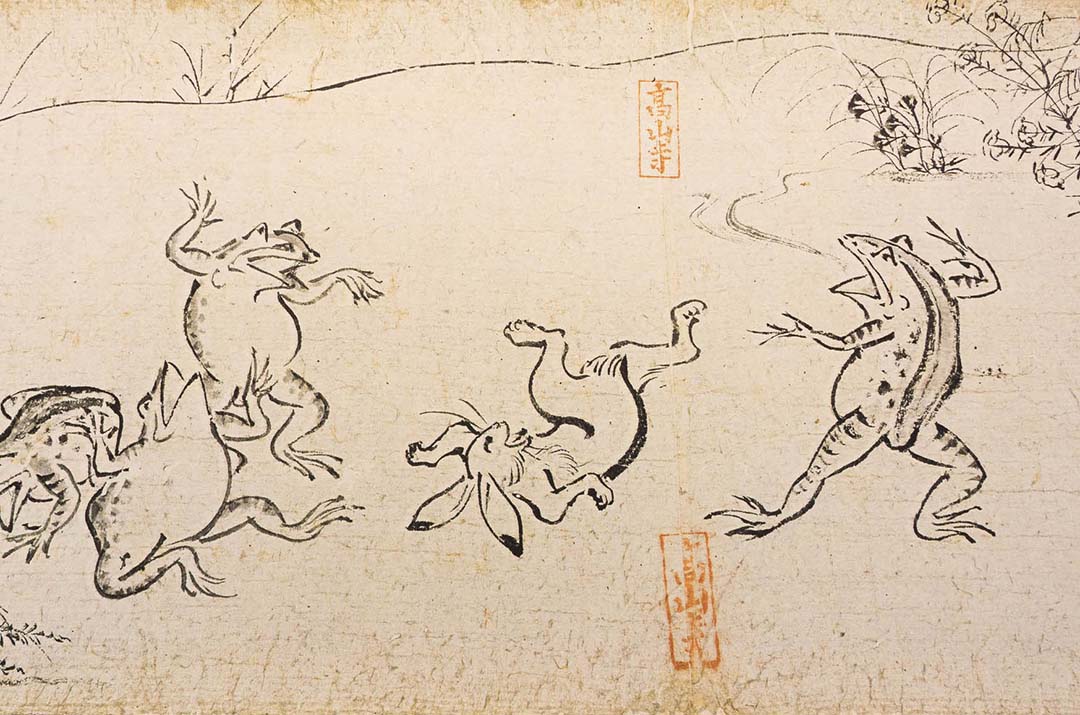

Credited as one of the first and oldest manga drawings, The Scrolls of Frolicking Animals (Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga) is a collection of picture scrolls dating as far back as the 12th century. The Chōjū-giga scrolls represent an early form of satire and depicts comical scenes between human-like forest animals, such as rabbits, monkeys, and frogs.

These drawings were created using a linear monochrome drawing style, similar to modern manga, and present vivid facial expressions, as well as techniques to simulate movement and early examples of speech bubbles. Many of these methods are still currently used in the creation of manga, therefore it is easy to see how these practices may have been passed down and have evolved through time.

Following Japan’s seclusion between the 1630s and 1853, the country’s economy saw a period of fast economic growth. It was during this time of isolation that many unique aspects of Japanese culture were encouraged, including the art form of ukiyo-e.

Ukiyo-e refers to a style and genre of Japanese art that takes the form of painting woodblock prints. These prints often depicted everyday people and were very popular among the nouveau riche merchant class.

Elements of this art style are carried on in manga today, such as the flatness and lack of three-dimensionality in illustrations, as well as the objective of creating a product destined for large consumption. Ukiyo-e was key to developing unique art trends, and much like manga today served as a way to promote Japan’s cultural heritage to the West.

Soon after, once Japan opened up to international trade, the first newspapers began circulating in response to the arrival of foreigners in the country. One of these publications, Japan Punch, a satirical comic magazine and journal, was created to mock the local Westerners and their difficulties in building commercial relationships with the Japanese. Japan Punch was illustrated and published by an English cartoonist and is regarded as one of the prototypes for future Japanese political cartoons. Indeed, satirical cartoons had a considerable influence on writers and artists of the time, who used the same type of means to criticize the Japanese government.

Another prominent form of illustrated literature during the Edo period (1603 to 1868) was kusa-zōshi. These publications were written in conversational Japanese and presented large illustrations depicting various themes based on different genres.

Kusa-zōshi included a variety of categories, such as aka-hon, kuro-hon, aohon, and kibyōshi, each characterized by the color of their book bindings. For example, Kuro-hon, or “black book,” covered themes like revenge, loyalty, and martial stories, while Ao-hon, or “blue books,” explored dramas from popular theatres and were split into two categories. One category was aimed at younger or less literate individuals, while the other catered towards more cultured adults.

Kibyōshi, or “yellow books,” were the most popular of the kusa-zōshi genres and are thought to be the first comic books in Japan written for adults, especially urban literate audiences, with the sole purpose of entertaining their readers. These illustrated novels were typically printed in ten-page volumes and reflected on aspects of contemporary society. Kibyōshi are considered to be manga’s close predecessor, specifically due to the style of framed pictures and other characteristics such as the use of dialogue balloons, which can still be found in current manga.

Early Aka-hon, or “red books,” were illustrated booklets made using woodblock techniques. They are considered the oldest form of woodblock-printed comic books and depicted children’s stories, fairytales, and folklore, therefore they were especially popular among children. However, the term aka-hon can also refer to popular post-war illustrated storybooks.

These red books were printed cheaply and were highly influenced by the late 1940s foreign media. Indeed, one of their defining characteristics was a complete disregard for copyright, and would often base their stories on established American characters. It isn’t hard to believe that this type of illustrated book would become very popular, given how Japan found itself under US occupation after World War II, and leave a big influence on the manga of today.

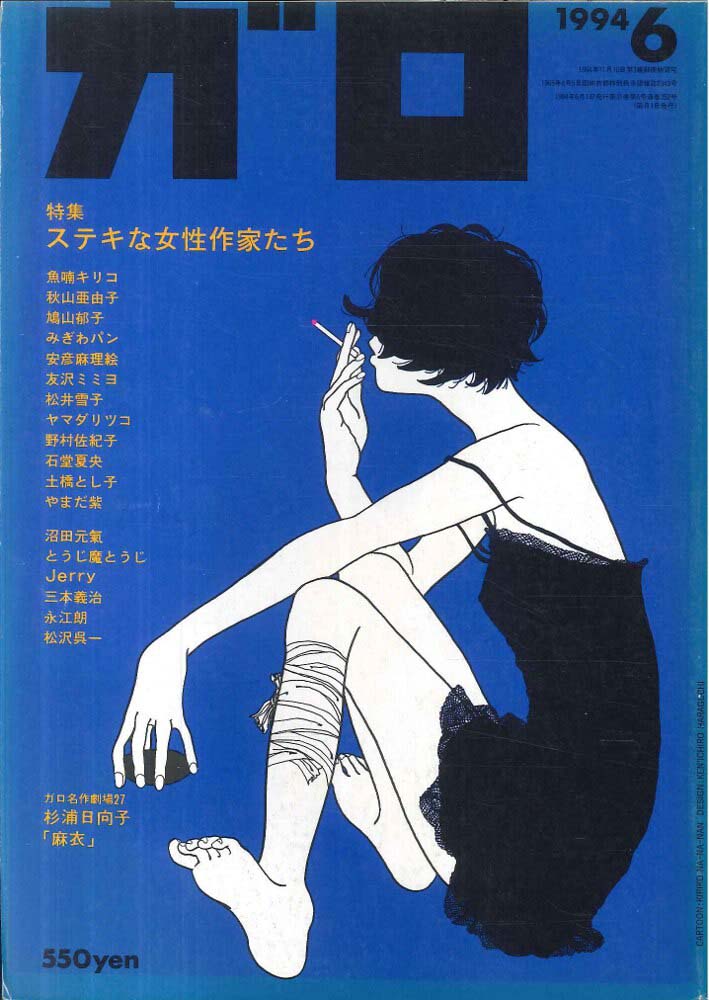

In the post-occupational years, Japanese artists developed their own unique style, which they published in newspapers and magazines up until they were granted their own weekly or monthly comic series. Monthly magazines like Garo presented avant-garde manga and went on to greatly influence the manga business and Japanese society.

Unlike past publications, it never established a set theme, instead explored a variety of topics and experimented with numerous artistic styles. It was during this period that a large manga readership was established, and in turn, a big marketing push for manga also took place. Comics became increasingly diverse and were developed according to the reader’s profile. Manga was created specifically for boys and specifically for girls and varied in categories based on age groups, and these divisions allowed for new developments.

Nonetheless, it was only during the 1980s and 1990s, after Japan’s economic boom, that manga became the colossal industry that it is today. This golden age of manga saw some of the most successful series take over the world, for instance, the manga One Piece, which has been running continuously since 1997.

Nowadays, Japanese manga continues to have a considerable artistic impact on comic artists internationally and has gone as far as influencing aspects of societal culture, not only in Southeast Asia but in many European countries as well. Therefore it is clear to see how manga is not just a product of our modern era, but an assimilation of old traditions and foreign forces. Yet what still remains a mystery is how the current manga economy will change comic books of the future.

You can learn more about the origins of Manga art and its many aspects by watching recordings of sessions from Wacom’s Manga and Anime Days 2021.